The Friends had another excellent speaker in Dave Joy who excelled at unpicking the social history and changes in cowkeeping in Liverpool. As he said it was a play in three acts, firstly the shifting of the farmers from the Yorkshire Dales – Hebden, in the case of Dave’s family who re located in the mid 1800’s attracted by the booming mill towns. Secondly there is the development of cowkeeping and the the milk industry and thirdly the mid 1900’s and the shifting of their roles to suburban milkmen.

Dave’s family history is interwoven with all these stories. The mass exodus from the dales not only led to Liverpool and other northern cities and towns but to new lives in parts of Europe, Africa, Canada and the US. Populations grew exponentially in the mid to late 1800’s in these northern towns and especially in the busy port of Liverpool. Although the railways brought in food, milk did not travel well and soured before reaching the customer.

Cow portrait. Norway. Attribution: Ernst Vikner

One bright Yorkshire spark had the idea of taking the cows to the city. Six to eight cows in full lactation would be brought from the home farm in the dales and rotated or sold on for beef as and when necessary. City herds were in a constant flux and were known as the ‘flying herds’. Their home was a byre however this wasn’t at a traditional long house farm but at the end of the row of terraced houses. The forms of some of these cow keeping houses can still be seen today for example ‘Battys Dairy’, however town planners eventually realised that purpose built cow houses were needed. People still remember the cows being driven on the highway to nearby fields and I can remember occasions when cows were herded through Burnley to the railway station.

Herding cows near Thoralby. Not quite Garston Liverpool. Attribution Malcolm Street

Dave recounted the work that the three generations of his family and others had to do to keep the cows in good condition and provide clean safe milk. In the dairy surfaces were cleaned and scrubbed, utensils sterilised. Cows were fed, watered, mucked out and then the milk had to be delivered. Before milk bottles, milk was dispensed from ‘kits’ straight into a jug also know as ‘kitting out’, something my Nana was used to as an adult she would buy ‘a quart o’ milk’. Rounds were sometimes twice daily.

You might ask how did the cows survive as opportunities for good grazing were few and far between?. There was access to fields for some cows however these canny Yorkshire farmers gleaned grass from the used grass cuttings in the park and verges. The port warehouses and factories were useful for spent grain from the brewers, molasses from the sugar refineries and oilseed cake which provided proven. The city saw mills were useful for sawdust for the byre floor and in the Old Haymarket, still there today, hay was exchanged for cow muck to the tune of £16K – in today’s money. Where there’s muck there’s brass indeed! This would have been a welcome bonus for the cities cowkeeping families.

Cowkeeping became an established part of the city economy and as other towns did Liverpool developed its own Cowkeeper Association. Social activities and outings for example to New Brighton beach meant that the next generation also married into similar farming families from the dales, which helped to keep the community alive. Quite often when they returned to visit the dales they told their relatives to ‘get themselves to Liverpool’.

Apparently there were ‘Cow Friday’s’ from Lime St. Station as cows from the countryside were herded through the streets and sold off along the way to the cowkeepers. It is to be imagined that if you were nearest the station you were able to select the choicest beasts. The railways also enabled competition to set up in the form of Corporate Dairies who collected milk from the countryside and were in direct competition with the cowkeepers. In 1881 37% of milk was corporate and there was dirty in-fighting, with the cowkeepers adopting marketing strategies such as “Fresh from the Cow”. Liverpool was the first place to develop ‘Cow keeping licences’ which their owners proudly displayed in their windows. They were keen to invite and welcome inspections by the public to demonstrate the quality of their milk. ‘Inspection invited’ became a cowkeeping mantra. At the annual shows there was fierce competition for the ‘Best kept dairy’, ‘Best kept Shippon’, Best Turn Out for Horse and Cart. Dave’s grandfather and father enjoyed turning out for these. The shows attracted thousands.

Dave recounted that the Joys came in two waves to Liverpool. First were Orlando, Hanna and George who stayed in the Penny Lane area. Daniel arrived from the Devonshire Arms Inn after being left a widower with five young children to bring up after the tragic death of his young wife. The dales folk brought with them a rural skills and a way of life that would have been useful in dealing with shippons that contained 20-30 cows. Garston became a useful place to live because of its proximity to the newly built canals.

The Joy’s celebrate 100 years in the Dairy Industry. Attribution: Dave Joy

World War 1 meant that the women were left to keep the cow keeping business running and they recruited help from their families in the dales. Business was affected as there was no good quality hay to be had. People had to adapt to survive and owners of any arable land including golf courses, parks, verges were asked to allow cows to graze or for the grass cuttings to be used for the cows. In WW11 dairies were sometimes mistaken for factories by the Luftwaffe and suffered accordingly.

In the interwar years and despite the Depression the Joys were relatively prosperous. The whole business of producing, bottling and delivering milk ensured that the money stayed in the family. A succession of Anthony Joy’s meant that the name of the shop didn’t have to be changed. Again a keen eye for a marketing opportunity led to one Joy advertising ‘Have you had the joy of Joy’s sausages?’.

Gradual changes, the building of housing estates which lessened opportunities for grazing and the introduction refrigeration which extended the shelf life of milk especially on the road and the creation of the Milk Marketing Board led to the third chapter in the working life of the Joy’s. They became suburban milkmen and after the last hay crop which meant that they had no horse and cart the business came to an end and so did the family involvement in cowkeeping, a way of life that had lasted from 1863 to 1963. One of the last families to be involved in cowkeeping were the Capsticks who continued until 1975.

Dairy Crest Milk Float.

Attribution: Brian Snelson

We are grateful to Dave for his exceptionally informative and enlightening talk without which many of us would have been totally unaware of the contribution of these families from the Dales to our great grandparents and grandparents daily life and health! If you want to know more read his books Liverpool Cowkeepers and My Family and other Scousers.

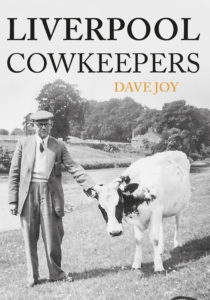

The front cover of Cowkeepers. Attribution: Dave Joy

And did you know?

Liverpool was the first city to experience cowkeepers, it also had the highest number – 6K and the longest running cowkeeping industry in England.

Other cities also had cowkeepers and in large numbers too, Burnley had around 700.

If you are interested in reading more about cowkeeping see also: http://www.johnhearfield.com/Cowkeeping/Cowkpr2.htm, http://www.johnhearfield.com/Cowkeeping/Cowkpr_Intro.htm